The first week of the Trump administration may signal a tough road ahead for agriculture. First, the president withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership treaty, which was expected to boost U.S. agricultural exports by more than $7 billion annually over the coming decades by dropping trade barriers among 12 North American and Asian economies, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Four days later, Trump administration officials said the U.S. could finance a new wall on the Mexican border through receipts from a 20% tax on Mexican imports. That appears to be part of a broader corporate tax overhaul, which would dun goods imported from every country.

The announcement, followed by a flurry of clarifications and caveats, set off worry that the U.S. was embarking on a trajectory that could lead to a trade war. That could hit home especially hard for U.S. farmers, who get about 20% of their annual revenue from trade — much of it from the very countries Trump could target.

If Trump embarks on negotiating a bilateral trade policy country by country, he likely would start with the 103 countries that sell to the U.S. more than they buy from American factories and farms. They range from China, with whom the U.S. has a $294 billion deficit, to Western Sahara, which exported $7,066 more than it imported last year.

Trump’s policy presents a conundrum for farmers and ranchers, a traditionally Republican constituency that supplied him with key support in swing states.

The countries with the worst trade imbalances happen to be among agriculture’s best customers, including two of Trump’s perennial punching bags: China and Mexico.

Overall, U.S. agriculture and related products amassed a $5-billion surplus worldwide, according to the USDA.

As a result of the 14 free trade agreements the U.S. signed with 20 countries, exports of grains and feeds, dairy products, poultry, beef, pork, fruits and vegetables each experienced growth of more than 15% since the 1990s, according to the USDA. Now, more than half the U.S. production of wheat, rice, cotton and nuts is sold abroad.

Meanwhile, some 85% of the fish we consume comes from abroad, while imports account for 19% of all U.S. food consumption.

Soybeans, corn, beef and nuts are among the top agricultural products exported to countries with the highest overall trade imbalances. Soybeans alone accounted for three-quarters of the agricultural trade surplus with China.

Whether these countries would enact retaliatory taxes depends on many factors — not the least of which is whether they can afford to find substitutes or grow the products themselves. China, which gets about a quarter of its agricultural imports from the U.S., will find both prospects difficult.

Food items figure strongly in trade wars, largely because the effects of price increases and shortages are felt quickly and acutely.

For example, the 90 retaliatory tariffs Mexico enacted from 2009 to 2011 in response to the U.S. refusal to allow its trucks to cross the border were disproportionately aimed at U.S. agricultural products. More than half of the estimated $984 million damage in U.S. sales to Mexico fell on agriculture, according to USDA economist Steven Zahniser.

So if the U.S. taxes vegetables and fruit from Mexico, fish from Asia or wood from Canada, those countries could dun our almonds, pork and corn — leaving more of them on the domestic market and dropping their price. A strong dollar last year effectively did the same thing, cutting into farm profits, but also causing the first annual deflation in supermarket food prices since Lyndon Johnson was president.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Services

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE

GOVERNMENT RELATIONS

BUSINESS & BROADER MARKET ACCESS

Upcoming Events

‘A WORKING LUNCH WITH NORDIN’: NATIONWIDE TOUR WITH TOYOTA

MGBF Roundtable: Digitalisation of the Food and Beverage Industry

THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: A THREAT OF DISRUPTION FOR BUSINESS?

FOOD SECURITY IN THE BREACH: INDUSTRIALISATION AND WEAPONISATION

MGBF In The News

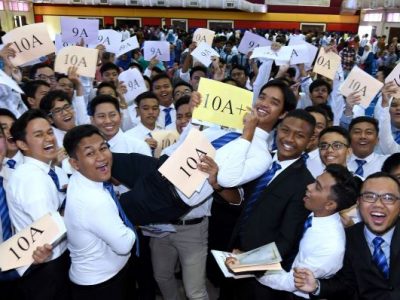

SPM and the Future of Data

MGBF Roundtable to shape Malaysia’s future in the digital economy

MGBF: Political stability to usher in new era for business

Death by a Thousand Algorithms

KSK Land recognised for investor attraction strategy

KSK Land set to drive further investment into Malaysia

A Need for Strategic Calm

With Change Comes Opportunity

MALAYSIA GLOBAL BUSINESS FORUM TIES UP WITH SCOUTASIA